Archaeological Site Significance & Eligibility Evaluation (Phase II)

Under Cultural Resource Management Basics, we learned what a cultural resource is, who assesses it and how, and when a discovery might represent a development constraint. Now, if our research, field survey, and reporting identify a built resource or archaeological site that is 45 or more years old and that meets one of the eligibility criteria for National Register or California Register (for local listing), then that site is a “historic property” under Section 106 of the NHPA (federal regulations) or a “significant historical resource” under CEQA (state or local rules). We have already gone over the four eligibility criteria (the same for Section 106 and CEQA), but as with everything in this field, there are nuances.

Please contact us if you have specific questions or scenarios you’d like to discuss.

Old buildings and other built environmental resources like bridges are evaluated differently.

As we said under Cultural Resource Management Basics, a significant cultural resource (which we now know as a historic property or a historical resource) is one that is eligible for the National Register and/or the California Register because:

It has demonstrated a connection with important events or people (Criterion 1/A and 2/B)

It exhibits distinctive characteristics (Criterion 3/A)

It has information/data potential (4/A)

As a general rule, buildings can only be eligible for the first three criteria and archaeological sites are only eligible for the fourth criterion-data potential. Exceptions to the rule would be things like buildings or factories with data potential or those that become ruins/archaeological sites, or archaeological sites that can be connected to important events etc., but we are going to set those aside for now. We don’t think we can explain the gray area better than the National Park Service, who has applied a lot of cogent thinking in its document How to Apply the National Register Criteria for Evaluation. And if you want a lot more background in identifying, recording, and evaluating cultural resources under CEQA specifically, take a look here .

Let’s start with archaeological sites and info/data potential.

Probably the most common and the most enduring prehistoric archaeological site around the world is the lithic scatter, so we will use that as our example. A lithic scatter is a surface or buried deposit of waste and/or tool material left behind by people testing the efficacy of stone tool material or manufacturing chipped stone tools such as arrowheads, dart or spear points (aka projectile points), hand axes, scrapers, blades, drills, awls, and so on. Most lithic scatters are waste flakes, or debitage, and to the untrained eye just appear to be a scatter of broken rocks (which indeed they are) but a field archaeologist can differentiate between a rock that has broken from natural processes and one that has been broken by a human on purpose.

Envision a surface lithic scatter with between 10 and 20 waste flakes taken from one piece of stone. It takes a flint knapper about a minute or so of hammering on a piece of obsidian or jasper to leave behind 20 waste flakes, and often that’s all it is – someone stopped for a minute, picked up a promising looking rock, hit it with another rock (a hammerstone) and walked away carrying the useful flakes and leaving the waste behind. Or maybe they decided none of it would be useful and just left it all behind. That rock scatter can remain on the surface for a long time – sometimes many hundreds or thousands of years. These sites are common. When the field archaeologist identifies such a resource, it is documented and given a unique number so that it goes into the record, but other than the observable surface items (e.g., type of rock, size of scatter) there may not be any further data potential. But it also could be associated with other things that have become buried and may be significant (i.e. contain important information, when interpreted correctly).

How do we find out? What do we do next?

First you write a research design to establish potential research themes, research questions, and data requirements that must be met to answer such questions. Site integrity and the ability of the site to satisfy these data requirements will be vital to answering said questions. The research design (sometimes prepared in support of a cultural resources treatment plan or other such document) will also propose surface collection and excavation. The document will be distributed to the developer/owner, the lead agency, and participating Native American entities for review.

Once the details are accepted by the lead agency, you have to look under the ground.

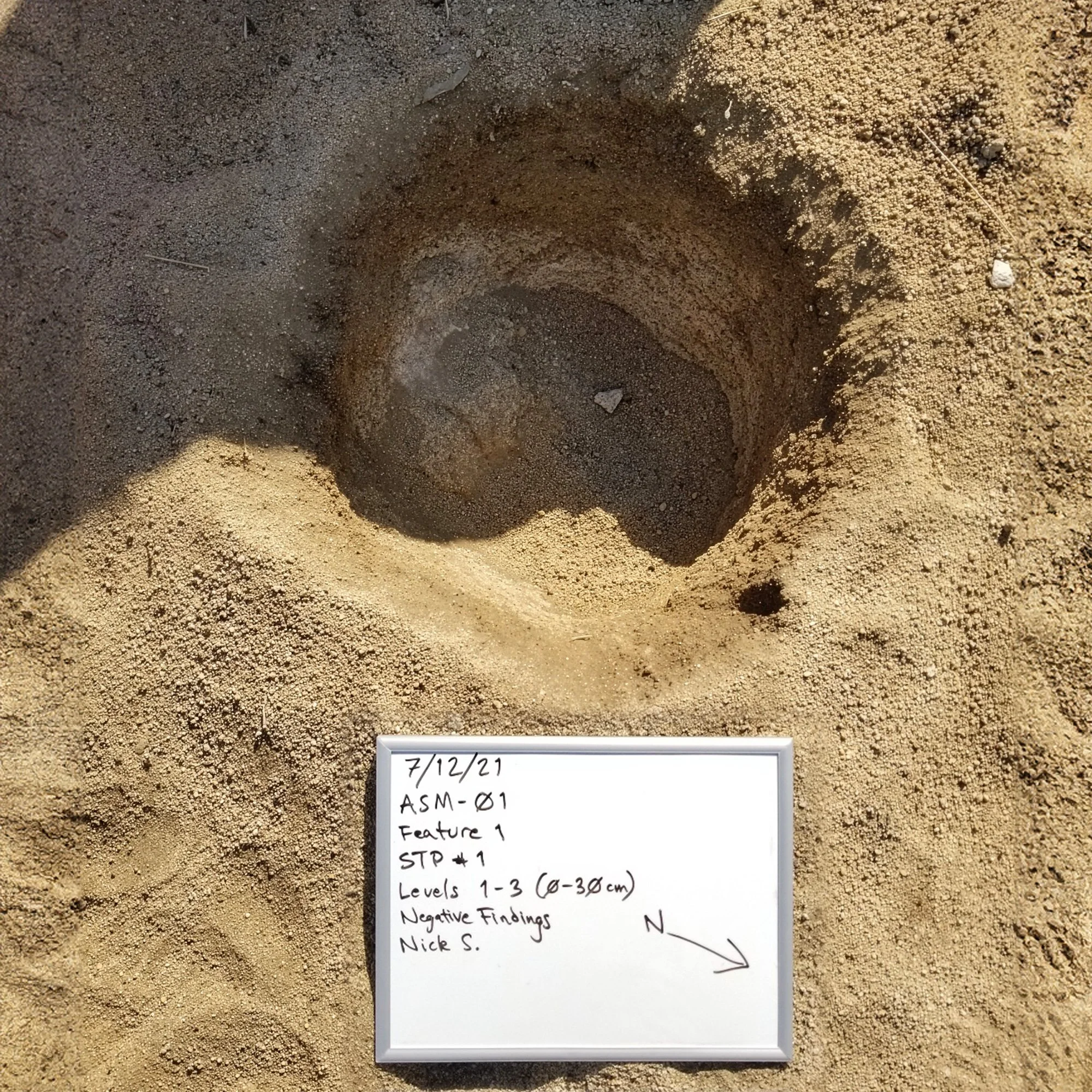

There are lots of ways to do this (shovel scrapes, judgmental units, auger pits, backhoe trenches, etc.) but we will discuss the most common way that archaeologists explore what lies beneath the surface: Excavating Shovel Test Pits (STPs).

Shovel Test Pits are a standard archaeological survey method to map potential cultural sites before larger digs.

Although STP sizes can vary depending on conditions and requirements, for our purposes an STP is a 30-centimeter diameter hole that is excavated with a shovel at regular intervals (10-20 cm at a time) and the dirt is sifted through a steel screen (usually 1/8th inch mesh). We record the exact location of the STP and document the type of sediment and cultural material (i.e. artifacts) that appear in the screen. If we dig and document an adequate number of STPs in the same fashion and we don’t find any evidence of intact buried cultural material (i.e., has not been disturbed by human activity since being deposited), the site does not have data potential and it is not eligible under criterion 4/D.

Under that scenario, we write up the results in a formatted technical report, demonstrating that there is no data potential and that the site cannot answer important research questions. At that point, you are finished, although since you have only sampled the site (not dug up every inch), archaeological and/or tribal monitoring will be a likely requirement during construction excavation.

But if the STPs yield something cultural that is intact and buried (or in situ), like a pile of cobbles with some ash or charcoal and burned bone mixed in (i.e., evidence of cooking) and maybe some lithics from the same stone tool material that we found in the surface scatter, then the site has data potential and it is eligible under criterion 4/D. Testing is concluded and we write up the results, recommending one of two options:

Preserve the site, if feasible (prioritized under most cultural resource regulations), or if preservation isn’t possible,

Complete data recovery excavation (sometimes called Phase III), or mitigation.

Complete Data Recovery Excavation (Phase III)

Before carrying out the data recovery excavation, the research design is re-examined or updated based on Phase II results to include a plan for more careful and systematic excavation.

Please contact us if you have questions or would like to talk through specific scenarios.

Is more analysis needed?

When excavation is complete, it is time to decide if any discoveries should be subject to specialized analysis (e.g., carbon dating, obsidian dating and sourcing, faunal analysis, botanical analysis, etc.). These analyses can tell us what the people at the site were cooking and if they were hunting, gathering, fishing, or farming, and when the activities were taking place. We can use this information to make statements about site interaction, trade, settlement patterns, and so on. The results of the data recovery/Phase III will be written up in a final report that presents all of the findings

Excavation and recovery

If the STPs (or other testing methods) have done their job, you should know where the sensitive areas are so that a larger sample can be excavated. The data recovery will usually involve excavating one by one-meter units at 10-centimeter intervals (and sifting the dirt through 1/8-inch screen mesh) to collect material or expose features for analysis, thereby exhausting the site’s data potential.

The Archaeologist / Cultural Resource Management Team’s Responsibility

In Cultural Resource Management it's important to remember that the archaeologist’s role is to make recommendations consistent with the requirements of Section 106, CEQA, and whatever other regulations we are operating under. The lead agency will make a determination or finding after they have received a recommendation in an appropriately formatted report. If a lead agency doesn’t have personnel equipped to review a cultural resources report, they may ask for a peer review from another cultural resource professional before making a determination. So an archaeologist may recommend that a Phase I: Assessment & Inventory has identified a potentially-eligible archaeological site (i.e., one that requires eligibility or significance evaluation) but the agency must accept that recommendation before the project moves to evaluation or Phase II: Survey & Inventory, and if necessary, Phase III: Data Recovery.