Prehistoric Ceramics

Coiling Pottery (Ancient Pottery 2025)

This article was written to describe prehistoric ceramics with a particular focus in western Riverside County. It has appeared elsewhere in the Cultural Setting sections of several cultural resources reports for projects near the City of Hemet which had high densities of prehistoric archaeological sites.

Fragments of the Past: What Ancient Ceramics Reveal About Early Civilizations

Prehistoric or aboriginal ceramics include both "utilitarian and non-utilitarian prehistoric or protohistoric objects composed of clay and other organic and inorganic materials fired at relatively high temperatures typically between 600 and 1000 degrees C (Sutton and Arkush 1998:109). For optimal strength, plasticity, and permeability ceramics will ideally contain clay particles measuring less than two thousandths of a millimeter and contain hydrous aluminum silicates and irons, alkalies, and alkaline earths. Clay is moldable when moist but becomes harder and less permeable when dried or fired (Sinopoli 1991:10; Sutton and Arkush 1998:109). Similar to lithic artifacts, the durability of ceramics can make it a common indicator of prehistoric activity in a variety of depositional contexts.

Cahuilla Ceramic Vessel

(Native American Net Roots 2019) Figure 1

The ability of moist clay to hold a molded shape, known as plasticity, is vital to the manufacture of reliable vessels: this is determined by interactions between water and the clay particles, whose plasticity is typically optimized by small grain size (Sinopoli 1991:11). During firing, clay vessels lose their moisture (and therefore, plasticity) which causes shrinkage and allows the vessel to harden. To minimize irregular shrinkage, which distorts vessel shape and may result in breakage, non-plastic material known as temper is commonly added to clay. Temper can include sand, moss, crushed rock, shell, or potsherds (see Figure 2). Some tempers may occur naturally and are intended to distribute heat evenly throughout a vessel when fired, and interrupt incipient cracks (Sinopoli 1991; Sutton and Arkush 1998). Tempers and other impurities influence vessel strength as well as appearance. Fired vessels exhibit colors determined by the presence and distribution of iron and organic materials in combination with varying oxygen percentages (determined by firing contexts). Iron tends to appear red or brown in vessels fired in high oxygen atmospheres (oxidized) and black or gray in atmospheres lacking significant oxygen (reduced). Organic matter can burn away completely in oxidized contexts commonly leaving pores within the clay. It can also turn clay dark brown, black, or gray in reduced contexts. When iron or organic impurities are absent, fired ceramics tend to be white or cream colored.

Weathered Potsherds with Visible Temper from BCR Consulting Discovery in Indio, California. Figure 2

Among the most common New World methods of ceramic construction, which include modeling, coiling, and molding, coiling represents the dominant method utilized in interior Southern California. The coiling method was developed by many different people all over the world. It used long coils or wedges of clay beginning at the base of a vessel and working upwards (Sutton and Arkush 1998:112). Baskets were often used to support coils as molding templates, and the vessels were usually finished using the paddle-and-anvil technique.

The paddle-and-anvil technique consisted of beating the unfired vessel exterior with a flat object (typically a wooden paddle), while supporting the interior surface with a complimentary-shaped stone or clay anvil (Sutton and Arkush 1998: 112; see Figure 4). Beating the unfinished clay in such a manner served to thin vessel walls, smoothing out the surface and eliminating irregularities. This method often leaves a distinct set of concave impressions visible on the vessel interior. Scraping and smoothing represent the final techniques applied to an unfired ceramic vessel.

The Paddle and Anvil Technique (Ancient Pottery 2025) Figure 4

Decoration on prehistoric North American pottery commonly includes two techniques: slip and paint. A slip is "a fine coating of clay and water applied over all or most of the surface of a vessel before firing to produce a smooth surface" (Sutton and Arkush 1998:116-117). Broken potsherds will usually show any presence of slip in the cross section in which a vessel’s core color is bordered by a markedly contrasting colored thin border on the surface. Slip is often a vessel's only decoration but may also function as a smooth surface on which to paint. Painting, which involves adding mineral or organic color before or after firing, was commonly practiced on both slipped and non-slipped vessels.

Drying and firing represent the final stages of pottery production. Drying time varies according to environmental conditions, as well as vessel thickness and mineral makeup of its constituent clay. The drying period dehydrates a vessel at low heat, reducing buildup of steam while firing and consequently reducing breakage. Drying is followed by staged firing, during which medium heat oxidation wipes out organic or carbonaceous material and is followed by high heat vitrification (Sutton and Arkush 1998:117-119). New world ceramicists, and particularly those in Southern California's interior, did not use kilns and therefore could not produce heat adequate for the conversion of clay to a uniform glass-like solid, or true vitrification. Rather, they practiced open firing which was accomplished by placing a dried, unfired vessel or vessels directly on a slow burning fire and burying them with additional fuel and/or an insulating layer of ceramic waste sherds. Vessel firing continued until the fuel was expended. Low-fire methods were exclusive to pre-contact southern California and only produced terracotta wares – those fired at temperatures below 900 degrees Celsius (Sinopoli 1991:29).

Most ceramics in southern California’s interior are probably a result of Patayan influence.

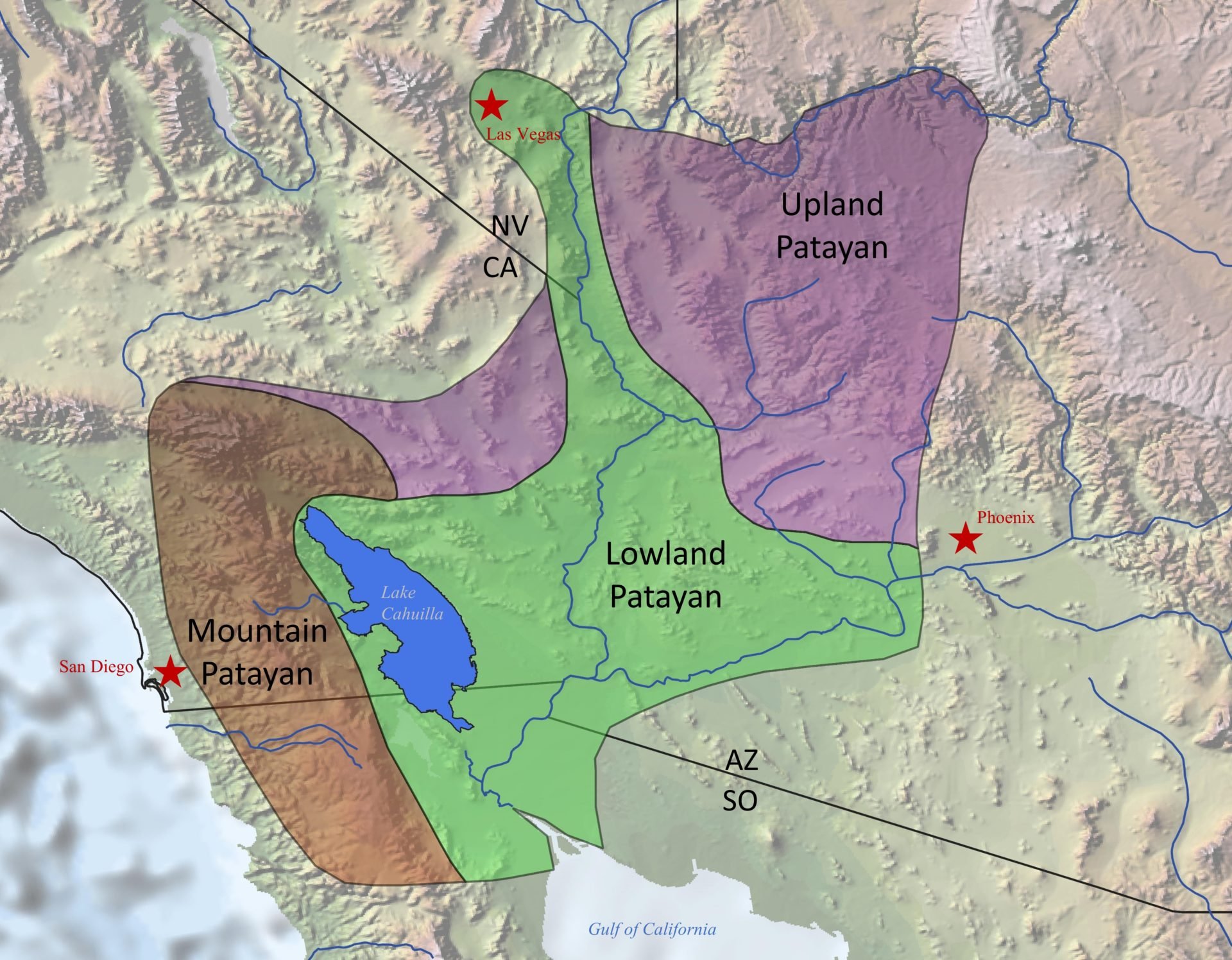

Although some evidence exists to attach significant antiquity to local ceramics (i.e. 8,090 +/- 50 C-14 years before present; see Cannon and Lerch 2007:6) most ceramics in southern California’s interior are probably a result of Patayan influence. The Patayan were Yuman speakers that settled the portions of the western Sonoran Desert around the Colorado River within present-day southern Nevada, southeastern California, and western Arizona between about A.D. 700 to 1550. Members of small, highly mobile bands, the Patayan cultivated corn, beans and squash that relied on flooding (rather than extensive irrigation works) of the Colorado River flood plain. They also hunted, fished, and collected mesquite beans and other native plants. The Patayan have been credited with the Sonoran monumental landscape art known as ingaglios or geoglyphs, some of which appear as human, animal, or geometric images large enough to be visible in aerial imagery along the Colorado River. Present descendants of the Patayan include the Mojave and Quechan peoples who currently occupy the Colorado River Indian Reservation and the Fort Mohave Indian Reservation (Sharp 2002).

The Patayan pattern of ceramics is generally accepted in three phases (see also King and Casebier 1981; May 1978). These are indicated by particular features, summarized here from studies of Lower Colorado Buffware Pottery presented by O'Neill (2003). Patayan I commenced approximately 1,200 years ago in southern Arizona along the Colorado and Gila rivers (Warren 1984) and closely resembles the Hohokam traditions to the east. Patayan I vessels all have a direct rim (i.e. the rim contains no curvature; O'Neill 2003:4) and the Colorado shoulder is a common though not ubiquitous feature. The Colorado shoulder disappeared completely during Patayan II, and rims were invariably recurved, or re-curled back on themselves during both the Patayan II and III phases. Patayan II first appears at a time in which Lake Cahuilla was likely full, approximately 950 years ago. At this time people produced pottery on both the eastern and western shores. Patayan III begins with the recession of Lake Cahuilla approximately 400 years ago and extends into the historic period. Patayan archaeological remains are relatively ephemeral and elsewhere, its culture has been conceptualized based on regional variations of material culture that have not been assigned to time periods (Wright 2020; see Figure 5). (For detailed models of Lake Cahuilla’s cycles of filling and drying, refer to Laylander 1997; Rockwell et al. 2022; Waters 1983; Wilke 1978). For a detailed discussion on stratigraphy of a prehistoric site at Lake Cahuilla, see Shepetuk 2025.)

Figure 5. Map Showing Patayan Areas

Ceramic artifacts are categorized by ware or class of pottery in which the individual vessels share similar technology, constituent clay or paste, and surface treatment. The Patayan pattern of ceramics is organized into Patayan Buff Ware and Brown Ware ceramic types. These include Colorado Buff Ware originating near the Colorado River and within the Lower Sonoran Life Zone of the eastern Peninsular Range foothills, Tizon Brown Ware commonly found in the Peninsular Range in western Riverside County, and Salton Buff and Salton Brown Wares from the shores of ancient Lake Cahuilla (Pritchard Parker and Horne 2001:105; Schaefer 1994:4). Buff Ware is locally produced from secondary deposits of sedimentary clays of Colorado Desert origin. These have commonly been attributed to Miocene marine deposits, lacustrine deposits near Lake Cahuilla, and local sedimentary deposits from basins and pans as well as the Colorado River flood plain (Pritchard Parker and Horne 2001:106), Clays used to produce local Brown Ware vessels come from primary residual clay deposits mainly derived from decomposing granite, but also include limestone, shale, and volcanic sources.

Clays used to produce the common wares of Southern California’s interior are ubiquitous and as a result, specific associations (i.e. '"Tizon Brown Ware" and “Lower Colorado Buff Ware") are problematic (see Figures 6 and 7). Furthermore, few exact mineral profiles and petrographic analyses connecting prehistoric ceramics with clay sources have been conducted locally, making cross-regional comparative analyses and true sourcing nearly impossible (Pritchard Parker and Home 2001:106). Although variable temperature firings and heterogenous ingredients within individual vessels also make explicit associations difficult, detailed examination using a l0X hand lens on clean-break potsherds can help group local types by temper and paste grain size. To form categories within locally acquired assemblages, past studies have used the Kent State soil particle size and sorting reference card to determine temper size and shape and Munsell Soil Color charts to distinguish color (Pritchard Parker and Horne 2001:108; Pritchard Parker 1991:78-79). Rim sherds are commonly analyzed using a rim and lip classification scheme developed by the Northern Arizona State University Museum (Pritchard Parker and Home. 2001:108; Pritchard Parker 1991:78-80; Colton 1953).

Colorado Buffware (San Diego Archaeological Center 2025) Figure 6

In addition to description of paste, temper, surface treatment, and firing, vessel form and function represent an important category of knowledge imparted by ceramic vessel analysis. When remnant portions of a vessel (or potsherds) are adequate, reconstructions of vessel mouth, diameter, and height may be projected (Sutton and Arkush 1998:124). A rim sherd for example can be fitted to a standard measurement template to determine orifice diameter and potentially vessel form and often function. If enough sherds are assembled, and in some cases fit together to recreate larger portions of individual vessels, a predictive model can be produced to illustrate rim sherd profiles along with a likely corresponding parent vessel.

Colorado Brown Ware (San Diego Archaeological Center 2025) Figure 7

Typological classification and form and function analysis serve several purposes, as well as exposing inherent limitations. Ceramic classification can help identify types within a particular region and can help determine temporal and spatial associations and interactions between prehistoric sites. Variation occurring within and between regional types can help answer questions about trade, migration, and social organization (Sutton and Arkush 1998). Ethnographic information, oral tradition, and the modern practices of extant Native American groups can also inform ceramic studies. However, the scrutiny of any cultural practices of pre-contact groups whose living descendants are many generations removed from practitioners should also rely on material analysis rather than history and ethnography alone. Such typology is often speculative and can be subject to biases of the analyst.

References

Ancient Pottery

2025 Ancient Pottery. Electronic Document: https://ancientpottery.how/how-to-make-a-coil-pot/. Accessed September 22, 2025.

Cannon, Amanda and Michael K. Lerch

2007 Unpublished Site Record for Temporary Site Number TVOL-22. On File at Statistical Research Incorporated. Redlands, California.

Colton, H.S.

1953 Pottery Analysis. Flagstaff. Arizona: Museum of Northern Arizona Ceramic Series No. 2.

King, C. and D.G. Casebier

1981 Background to Historic and Prehistoric Resources of the East Mojave Desert Religion. Archaeological Research Unit, University of California. Riverside. Prepared for lJ.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, California Desert Planning Unit. Riverside, California.

Laylander, Don

1997 The Last Days of Lake Cahuilla: The Elmore Site. Pacific Coast Archaeological Society Quarterly 33(1 & 2):1–69.

May, R.V.

1978 Southern California Indigenous Ceramic Typology: A Contribution fo Malcolm J. Roger’s Research. Archaeology Survey Association of Southern California Journal 2 (2).

Native American Net Roots

2019 Cahuilla Pottery (Photo Diary). Electronic Document: https://nativeamerican netroots.net/diary/Indians-101-Cahuilla-Pottery-Photo-Diary. Accessed September 22, 2025.

O’Neill, Colin

2003 Ancient Pottery in San Diego County. Electronic Document: http://www.piconova. net/coneill/sdcaveceramics/sdcaveceramics.htm. Accessed June 25. 2007.

Pritchard Parker, Mari A.

1991 Analysis of Prehistoric Ceramics. In Phase Ill Archaeological Mitigation Data Recovery at Prehistoric Sites CA-RIV-2199 and CA-RIV-4168 El Mirador Professional Plaza, Prepared by Richard Cerreto, pp. 78-92. Archaeological Research llnit University of California. Riverside.

Pritchard Parker, Mari A. and Melinda Horne

2001 Native American Ceramics ln Eastside Reservoir Project Final Report of Archaeological Investigations Volume V: Technical Studies. Edited by Susan K. Goldberg. Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, pp. 105-128.

Rockwell, Thomas K., Aron J. Meltzner, Erik C. Haaker, and Danielle Madugo

2022 The Late Holocene History of Lake Cahuilla: Two Thousand Years of Repeated Fillings within the Salton Trough, Imperial Valley, California. Quaternary Science Reviews 282(107456).

San Diego Archaeological Center

2025 Artifact of the Week: Pottery Sherds. Electronic Document: https://sandiego archaeology.org/artifact-of-the-week-pottery-sherds/. Accessed September 22, 2025.

Schaefer, J.

1994 The Stuff of Creation: Recent Approaches to Ceramic Analysis in the Colorado Desert. In Recent Research along The Lower Colorado, edited by J .A. Ezzo, pp. 1-27. Statistical Research. lnc. Technical Series 51. Tucson. Arizona.

Sharp, Jay W.

2002 Life on the Margin. Electronic Document: https://www.desertusa.com/ind1 /ind_new/ind15.html. Accessed September 29, 2025

Shepetuk, Nick

2025 Stratigraphy: Recovering Data in the Low Desert. Electronic Document: https://www.bcrcllc.com/blog/stratigraphy-recovering-data-in-the-low-desert. Accessed multiple dates.

Sinopoli, Carla

1991 Approaches to Archaeological Ceramics. Plenum Publishing Corporation. New York.

Sutton, Mark Q. and Brooke S. Arkush

1998 Archaeological Laboratory Methods an Introduction. Second Edition. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company, Dubuque, Iowa.

Warren, C.N.

1984 The Desert Region. In California Archaeology, by M.J. Moratto, pp. 339-430. Academic Press. Orlando and London.

Waters, Michael

1983 Late Holocene Lacustrine Chronology and Archaeology of Ancient Lake Cahuilla, California. Quaternary Research 19:373–387.

Wilke, Philip J.

1978 Late Prehistoric Human Ecology at Lake Cahuilla Coachella Valley, California. University of California Department of Anthropology. Berkeley.

Wright, Aaron

2020 Life of the Gila: The Patayan World. Electronic Document: https://www.archaeology southwest.org/2020/02/20/life-of-the-gila-the-patayan-world/. Accessed September 22, 2025.